A friend recently confessed that she was bored by a book she had read for a book club. Having just slogged through the same book myself, I agreed completely. As I writer, I knew exactly why the book didn’t work for me. But the woman I was chatting with couldn’t articulate why she hated the book. She just knew it was boring.

That got me thinking, of course. And as I result, I’ve come up with a list of approaches to make a novel as boring as you possibly can. If your goal is to provide an insomnia cure to the masses, search no further, for I have compiled some time-honored methods for making your book put-downable (all of which I’ve encountered in recent reading, unfortunately):

- Tell, don’t show. Tell us our hero is angry and scared. (“Bob was angry and sad.”) There’s no need to show us Bob’s trembling fists, flushed cheeks, or the way his eyes flick from bad guy to door to knife. We readers don’t need to see a scene come to life. We’re fine with the Cliff Notes version.

- Have characters explain everything, including comprehensive backstories, in page after page of long-sentenced dialogue, unbroken by anything like atmosphere, body language, setting, or a character’s inner contemplations. After all, everyone you know enjoys hearing everyone else speak in hour-long monologues full of mansplaining descriptions and strained metaphors.

- Make your character think about how they feel, then tell someone how they feel, then do something physical to show how they feel, all in the same paragraph. Triple redundancy works for the military, so it must work for characters, too.

- Neglect to describe the setting. Readers love imagining characters in a featureless beige box. Whatever you do, don’t use a vivid setting to hint at the conflict, build tension, set the mood, or reveal a character’s emotional state.

- Or, conversely, go ahead and describe the setting for page after page after page (preferably a whole chapter’s worth, if you can manage it). Explain in minute detail the landscape, the geology, the political system, any religions and their hierarchy, all relevant economic systems, and as a bonus, the weather, all without weaving any of that information organically into the story or into the character’s struggles so that we can see how it matters. Readers love info-dumps. They just can’t get enough of dry travelogues unhindered by plot or character.

- Use explicit, detailed stage directions because readers can’t possibly imagine how a character might step across the room without being told which foot they led with, which piece of furniture they avoided bumping into, and the exact angle at which they looked down upon the teapot. It’s best to assume the reader can’t picture what “walking across the room” looks like.

- Remember to introduce secondary characters with full names and full, rich, intriguing backstories, who then disappear by the next scene and are never heard from again.

- Or, introduce brand-new two-dimensional characters into random scenes, just in time to coincidentally solve a particular problem for our protagonist. Then they, too, can disappear by the next scene.

- Have only a vague sense of plot. Plot is annoying.

- And finally, make sure your character doesn’t participate in exciting events, solve their own problems, or overcome their own obstacles. It’s much more interesting to have those things happen off-stage, so that your character can just hear about them later through the grapevine. The best stuff always happens off-stage and behind closed doors, right? Letting your protagonist hear about them after the fact and second-hand is literary gold.

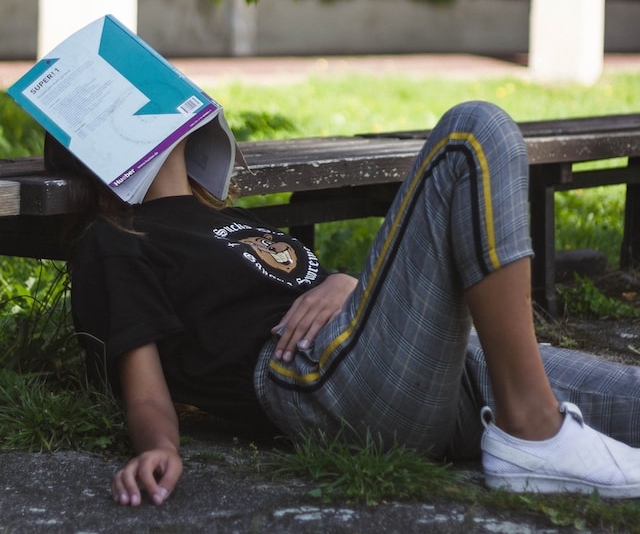

There you go. Now you know how to turn your masterpiece into a sleep aid. You can thank me later. Right now, I think it’s time to go take a nap.

[Photo by Tony Tran on Unsplash]