After high school, I enlisted in the U.S. Army for a three-year tour of duty. Never having traveled farther than a car trip from Colorado to Iowa, I took the train to basic training in Missouri. Before I completed basic, President Kennedy was assassinated, and our inexperienced platoon of raw recruits and reluctant draftees was issued live ammunition and ordered to guard the perimeter of our base. After the crisis passed, I rode a cross-country bus to my training site in Long Island Sound, New York. While attending my military school, I got a three-day pass and took my first airplane ride to Washington, D.C. A month later, I was on my way to San Francisco where I joined the staff of a monthly magazine which served the patients and staff of Letterman Army Hospital. A year later, I shipped out on a troop transport to Korea where I served as editor for the Bayonet Newspaper, a weekly publication of the 7th Infantry Division.

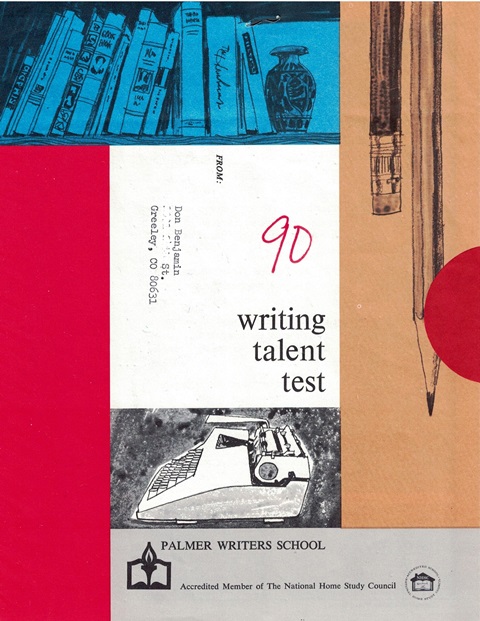

I mention my military experience because, as soon as I was honorably discharged, I returned home to Colorado with the idea of making my living as a writer. As an older-than-average but still impressionable college freshman, I saw a magazine advertisement for the Palmer Writers School. This now-defunct correspondence school invited prospective authors to take a rather mundane four-part test and send it in for evaluation, as stated in the brochure:

“The purpose of this test is to give you an estimate of your writing capabilities. We will grade your test and return it to you as soon as possible with our frank, expert opinion of your chances for success as a writer.”

I must have fallen for this offer because, while cleaning out my over-stuffed filing cabinet the other day, I ran across my old, graded test. In those days before personal computers, my answers had been carefully composed using a manual typewriter. I can’t recall what my expectations were, but apparently I completed the test, used the supplied gummed label to seal it, and mailed it to the school in Minnesota.

My test was eventually returned. I was given a score of 90 out of 100 and someone had written, in red cursive letters, a single pithy critique on each part: “Interesting, Appropriate, Sets mood, Perceptive.”

In the wake of my graded test, I undoubtedly received follow-up literature outlining the cost of taking the Palmer course. Whatever the price tag, as a starving college student, I’m certain I decided to pass.

I won’t risk lowering my score by reproducing the details of the squalid writing sample which I innocently mailed to Palmer more than half a century ago. However, I’ve reproduced Part A of that long-ago exam in case anyone would care to take a crack at it. Here it is:

“Part A. In the following paragraph from a published story, we have left out certain words. Read the selection carefully. Think about the mood and then write in the word that you think belongs in each blank.

She ____ her faded chenille robe around her as she _____ toward the door in her ____ slippers. The little dark eyes ____ suspiciously out of her ____ gray-crowned face. She seemed to ignore the ____ rose-strewn wallpaper, the ____ rag rugs and the white iron bed.”

These days, the online marketplace is awash with workshops, how-to videos, seminars, and virtual retreats aimed at writers. I didn’t take the Palmer course. I opted instead for four years of writing college term papers, followed by a masters’ thesis, followed by decades of on-the-job training as a college administrator, legislative policy analyst, and journalist.

Like a character in one of my novels, I sometimes wonder how my story arc would have changed had I enrolled in the Palmer Writers School. I wonder about how my life might have been different, how my fortunes might have altered. I wonder about these heady topics, but mostly I wonder why this once-famous school didn’t include an asterisk in its company name.