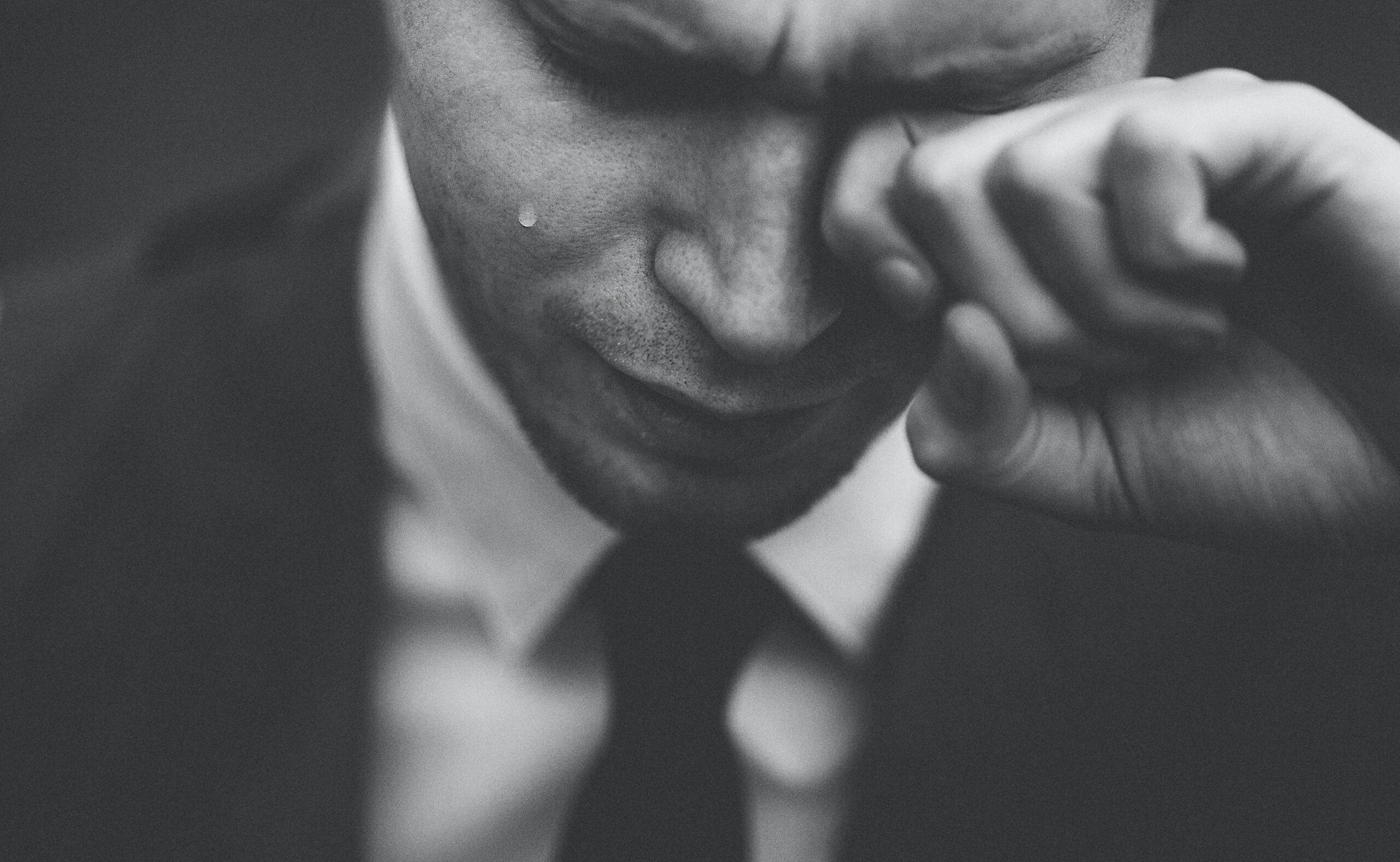

After playing with the Atlanta Braves for 12 years, Freddie Freeman signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers. Last month, he returned to Atlanta for the first time to play a game in his new uniform. And, according to almost every single account of the experience, he “got emotional.”

Okay, now, one of your jobs as fiction writers is to rise up out of your chair and scream at the television anytime you hear that some public figure or even some ordinary Joe or Jane “got emotional.”

Because, clearly, these reporters don’t feel they can come right out and say it:

He cried.

Or.

She cried.

Instead, it’s always “got emotional.”

Well, if you didn’t know the circumstances and had no idea what Freddie Freeman might have been feeling, you could also guess that he might have gotten extremely happy.

Right?

Joy is an emotion.

So is fear. So is anger. Or disgust.

I’ve leave it to the psychologists to parse emotions and feelings and how to categorize them all, but subsets of “sad” might include depressed or desperate, upset or sorrowful. Subsets of “hurt” might include jealous or betrayed, abused, or wounded. Isn’t “confident” an emotion? On and on. (One great breakdown on Emotions Vs. Feelings—and there is a difference—is this post by David Corbett.)

And the point is that these emotions drive our characters. More importantly, they drive their decisions about how to manage whatever turmoil we’ve thrown at them.

It doesn’t hurt to be explicit about what your characters are feeling—how they are reacting to the hailstones we are slinging at them and muck of misery we are forcing them to endure. Yes, better to show than tell (as always) but don’t shy away. Think this is the stuff of cheap romances or cookie-cutter works in any genre? Take a look at Kazuo Ishiguro and why he won the freaking Nobel Prize for Literature.

But just detailing emotion after emotion on the page won’t give readers what they are looking for. As David Corbett also notes, it’s the surprise emotion they encounter that will give readers that feeling of complexity. Of humanity. Of relatability.

Corbett:

“We all experience multiple emotions in any given situation. So, too, our characters. To create genuine emotion when crafting a scene, identify the most likely or obvious response your character might have, then ask: What other emotion might she be experiencing? Then ask it again—reach a ‘third-level emotion.’ Have the character express or exhibit that. Through this use of the unexpected, the reader will experience a greater range of emotion, making the scene more vivid.”

Because we know what we want our readers to do.

We want them, of course, to get emotional.

(PHOTO BY Tom Pumford on Unsplash.)