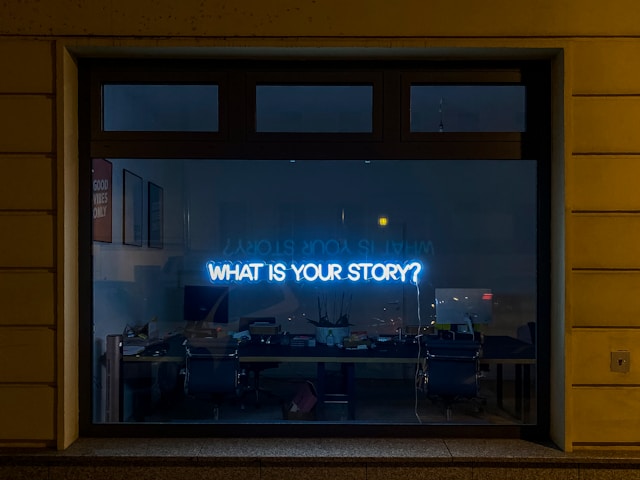

If you’re a writer, you’ll hear this question a thousand times before you finally brain someone and end up in jail:

“What is your story about?”

At writing conferences, retreats, pitch events, backyard barbeques, Thanksgiving dinner, the airplane when the passenger next to you asks what you do, and let’s face it, from your cellmate in prison after you murder the last person who asks it… people will ask you what your story’s about.

How do you answer? Do you ramble for thirty minutes about backstory, emotional arcs, and a dozen messy subplots until the person’s eyes glaze over?

Or do you give them your one-sentence logline, leaving them hooked and dying to read more?

Of course, we all know what the answer should be.

But loglines are hard. Torturous, even. So we avoid writing them, along with making dentist appointments and organizing our taxes.

But if you’re serious about this book you’re writing, maybe it’s time to create its logline. It’s especially helpful to have one handy if you’re headed to the upcoming Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers conference, or any other writing event, because you’re going to be asked “What’s your story about?” at least a dozen times before you finally drag your weary head home.

So let’s look at loglines.

A logline is a one-sentence description of the core or heart of your story. It describes your main character, the goal they’re desperate to achieve, the obstacle in their way, and the consequences if they fail. Oh, and it also conveys the tone of your story, all in around 25 to 35 words.

Easy-peasy, right? Okay, maybe not. But it’s manageable if we break the logline into its essential components. Then we can look at how to put them together into a sentence.

For each of the following logline elements, distill your description down to a few words (ideally, 2 or 3):

- Protagonist: Who is your main character? (If you have multiple main characters, who’s the one whose story this really is when it comes right down to it?) Don’t use their name. Instead describe the type of person they are with a noun (“astronaut”) and one or two adjectives (“grumpy, retired”). “Fred” doesn’t tell us who this character is, but “disgraced politician,” “overwhelmed kindergarten teacher,” or “perpetually upbeat mortician” does.

- Inciting incident: What event propels your character into action or turns this character’s life in a new direction? Examples: “an invitation to a wizard academy arrives,” or “the space station’s life-support system fails,” or “the circus elephant disappears.”

- External goal: What is the main character’s most important exterior goal—the visible or tangible goal that moves the plot along, like “land the new job,” “win the big game,” “overthrow the corrupt government,” or “rescue the lost puppy”?

- Interior goal: What is the character’s internal need, which they often don’t recognize about themselves, but which they’ll somehow have to resolve while they’re busy chasing their exterior goal? Examples: “reconnect with his estranged father,” “learn to fall in love again,” “forgive himself,” or “accept help from others.”

- Protagonist’s action: What must the character do—or what two things must the character choose between—to achieve their external and/or internal goals? Examples: “Score a perfect 10 on the balance beam,” “find the real killer,” or “choose whether to accept the promotion she’s worked so hard for or quit to travel the world with her sister.”

- Stakes: What does the protagonist stand to lose if they don’t achieve their internal and/or external goals? What will be the dire consequences if they fail, or if they succeed? Examples: “42 innocent people will die,” “lose the family farm,” or “do time for a crime she didn’t commit.”

- Antagonist: If there is an antagonist, describe them the same way you described your protagonist (1 or 2 adjectives and a noun): “a slimy used-car salesman,” “a clingy, insecure babysitter,” “a tiger-obsessed ex-girlfriend,” or “a Russian-backed mob henchman.”

- Antagonist’s action: What does the antagonist have to do to stop the protagonist from achieving their goals?

- Setting: If the setting is modern and not out-of-the-ordinary, you may not need to specify it in your logline. But if it’s important to your story, describe it here: “a sixteenth-century monastery,” “a deep-space prison ship,” or “a near-future boarding school for AI children.”

Now that you have a list of potential components for your logline, how can you fit them together into an intriguing sentence? You won’t necessarily use all the components. Some will be more important than others, while others can be eliminated altogether. Boil each element down to as few words as possible.

You’ll find lots of formulas for loglines online, and I’ll include a couple here. But there isn’t one single template for a logline that will fit every story, and the order of the components doesn’t matter. So try writing a dozen or more different sentences until you find one that feels right for your story. Move things around, eliminate some elements if they aren’t contributing anything, focus on different aspects of your story in each version of your logline.

A common formula I see is:

“When <inciting incident happens> in <setting>, a <protagonist type of person> must <protagonist’s action> to <achieve or choose between exterior and/or external goal(s)> before <stakes or consequences happen>.”

A slightly longer variation might be something like:

“When <inciting incident happens> in <setting>, a <protagonist type of person> must <achieve or choose between exterior and/or external goal(s)>, but when <conflict or antagonist> threatens to <antagonist’s action>, <the protagonist> must <protagonist’s action> before <stakes or consequences happen>.”

Peruse Amazon or GoodReads for books that are similar to yours (genre, tone, etc.), and see what their loglines sound like. If you’re still on X-Twitter, look for pitch events (like #pitmad), where people pitch their story in a single Tweet (basically a logline), and see which ones leave you dazzled and which ones leave you saying “meh.” And, of course, Google “logline examples” for tons of inspiration. But try to make your approach fresh, and try to match the tone of your logline to the tone of your book (humorous, ironic, threatening, whimsical, suspenseful, etc.).

If you’re still stuck, try this fun little pitch generator on Carissa Taylor’s blog: “Pitch Factory – Twitter Pitch Logline Generator.” And Graeme Shimmin has a formula he calls the Killogator ™ that he uses to generate pitches: “Writing a Killer Logline.” Neither generator worked terribly well for my own story, but they may at least give you some more ideas as you wrestle with yours.

Good luck putting together your logline. I can’t wait to run into you somewhere soon and ask you “So, what’s your story about?”

[Photo by Etienne Girardet on Unsplash]