A common misconception about chaos is that it’s chaotic, meaning the object in question is out of control, disorganized, irretrievably confused. Every writer has been there—the letters swim on the page like aimless tadpoles, every word you’ve written screams “YOU SUCK!” You get the drift. But, despair not! It turns out “chaos,” as used in the vernacular, does not mean what you may think it does. Chaos is not a synonym for random.

Chaos theory, the scientific version, not the layman’s interpretation, tells us that there are patterns in them there scribblings, that what may seem like a word stew beyond all hope has meaning buried in its depths. The good news is that patterns can, and do, emerge even in chaotic systems—in our case, a work in progress. All that is needed is enough iterations—in our case, edits—for such patterns, such as story and meaning. to become apparent.

So, how is it you ask, we find such hidden treasure and sculpt it into a compelling tale worthy of your talents and energy?

By thinking about the editing process as the lowly vegetable, the onion, is how.

Make no mistake, editing is a process and there is no substitute for doing the hard yards. But that does not mean editing has to be mayhem. And the process doesn’t have to be so complicated that you feel your head will explode. You can turn the editing maelstrom into a calm day at the computer or pad of paper by training yourself to focus on one thing at a time.

Science tells us that the human memory is able to keep five items, plus or minus two, in mind at once. Meaning the average homo sapiens can keep somewhere between five and nine items online simultaneously. So why do we try to manhandle plot and characterization and grammar, and… all at once? A more manageable approach is to refine the process by keeping one purpose in mind at a time, and in so doing, avoid tearing your hair out or, worse, abandoning said work in progress.

Editing is not like outlining. You can be a plotter or a pantster, or a hybrid, but all writers must be editors. Editing is not an option, unless you’re happy with the first (and, likely, worst) version of your work.

Be the prep cook and view the editing process as akin to peeling away the layers of an onion. By starting at the most general level and moving inward to the most specific, you will be best able to isolate and fix that which needs attention. In so doing, you’ll be able avoid the mental gymnastics of thinking about plot intricacies while considering the merits of the Oxford comma.

So, once you have a manuscript in hand and you’ve done the happy dance, what next? It’s time to narrow your focus and dive into editing!

- Wait! Put the manuscript away, be it in a drawer or computer file. Let the thing marinate. Let your brain decompress. It’s funny how it works, but when you free up brain space amazing things happen. Psychologists call this unconscious reordering of ideas “self-organization,” by which they mean order emerges out of disorder. Take a walk, a run, watch a favorite show, read a book, cook, do anything, just stay away from the manuscript no matter how it calls to you to fuss with just one more thing. For how long? Depends on your tolerance for leaving things unfinished, but, no matter what, do not dig the thing out until you are committed to moving your work from draft to finished product, otherwise, you’re time would be better spent on another project. Then, and only then, is it time to put your helmet on, jump back in the trenches, and start mining for treasure level by level.

- Pacing. First, put down the pen/mouse and read your story like a reader. Chapter by chapter, assess whether it moves at a speed appropriate for the genre and nature of the tale being told. Are there “flabby” points that could do with some tightening? Or spots where you zip through the action or character development too fast? Inconsistencies that nag? Unresolved plot points? Leave the reader breathless from too much action? Or bored to tears? You’ll find out fast if you read your own work as a reader will. Every story has a natural rhythm depending on both genre and plot, so make sure yours delivers.

- Point of View. What is/are the POVs in your story? Does a chosen POV serve the story well? Examine the manuscript for POV violations. Nothing is more distracting to a reader than suddenly hopping around in different characters’ heads. And even if we stay in one head at a time, does each POV character’s POV say what you want it to say, does it do the required heavy lifting needed for proper characterization?

- Show Don’t Tell. Enough said. We all know what the admonition means, or we should given how much real estate is given over to the topic in magazines, blogs, and at conferences. Suffice it to say, do a revision looking for all the “telly” parts of your work and fix them. Not that exposition is verboten, quite the opposite. Exposition is a useful tool, where appropriate, meaning for less critical elements of your story.

- Info Dumping/Backstory. No matter the acceptable word count in your genre, space is limited, so use one revision to troll for info dumps and backstory. Dumping information you, the author, think is important but really isn’t, has the effect of ripping readers out of the moment you have worked so hard to create. Just because you spent so long developing your protagonist’s backstory doesn’t mean it all needs to find it’s way into your manuscript. Backstory informs, it is not mission critical in most cases. Much like hot sauce, a little backstory goes a long way. Think brushstrokes. Trust your reader. Spoon feeding infantilizes readers. Readers are more than capable of filling in the blanks with minimal leading. It’s part of the reader/author contract, not to mention the fun of reading.

- Dialogue. Nothing reveals character quite like dialogue, and nothing says more about the skill of the author. The concept of dialogue seems simple enough. We all communicate in every day, albeit often imperfectly. Which is exactly the point. Does every snippet on every page serve a purpose? Have you missed an opportunity to convey subtext by making what your characters say too on the nose, too clear? Are your characters Chatty Cathys or Colins, just talking on and on because it’s time for you to break out of exposition or setting description? And perish the thought, but are you using dialogue not to develop character or plot, but to info dump information/lever in some backstory because you can’t figure out another way to get it in front of the reader? Bottom line, do a revision looking only at dialogue, its content, purpose, and verisimilitude to how humans actually communicate.

- The Sensory Experience. Have you given the reader the full sensory experience of the world you have created? When you edit, do one pass keeping in mind the use of all the senses. Do you rely more on sight and sound than touch or taste? It’s the writer’s job to paint as full as picture as possible of the world, and exploring how characters experience the world through their senses has the knock-on effect of doing the same for the reader.

- Clunker Patrol. Once you you’ve dealt with all the outer layers of your story, you’ll find yourself getting into the weeds, the details that make your story compelling and “real.” Images that fall flat. Awkward turns of phrase. Odd or inappropriate syntax. Characters who come off the page as flat or unidimensional. Does your story have too many incidences of author intrusion, i.e., where the reader will clearly see it’s the author speaking, not his people. Or, worse, are you preaching—you wrote this book, dammit, to make a point and so you’re going to make it again and again. Preaching is not story telling.

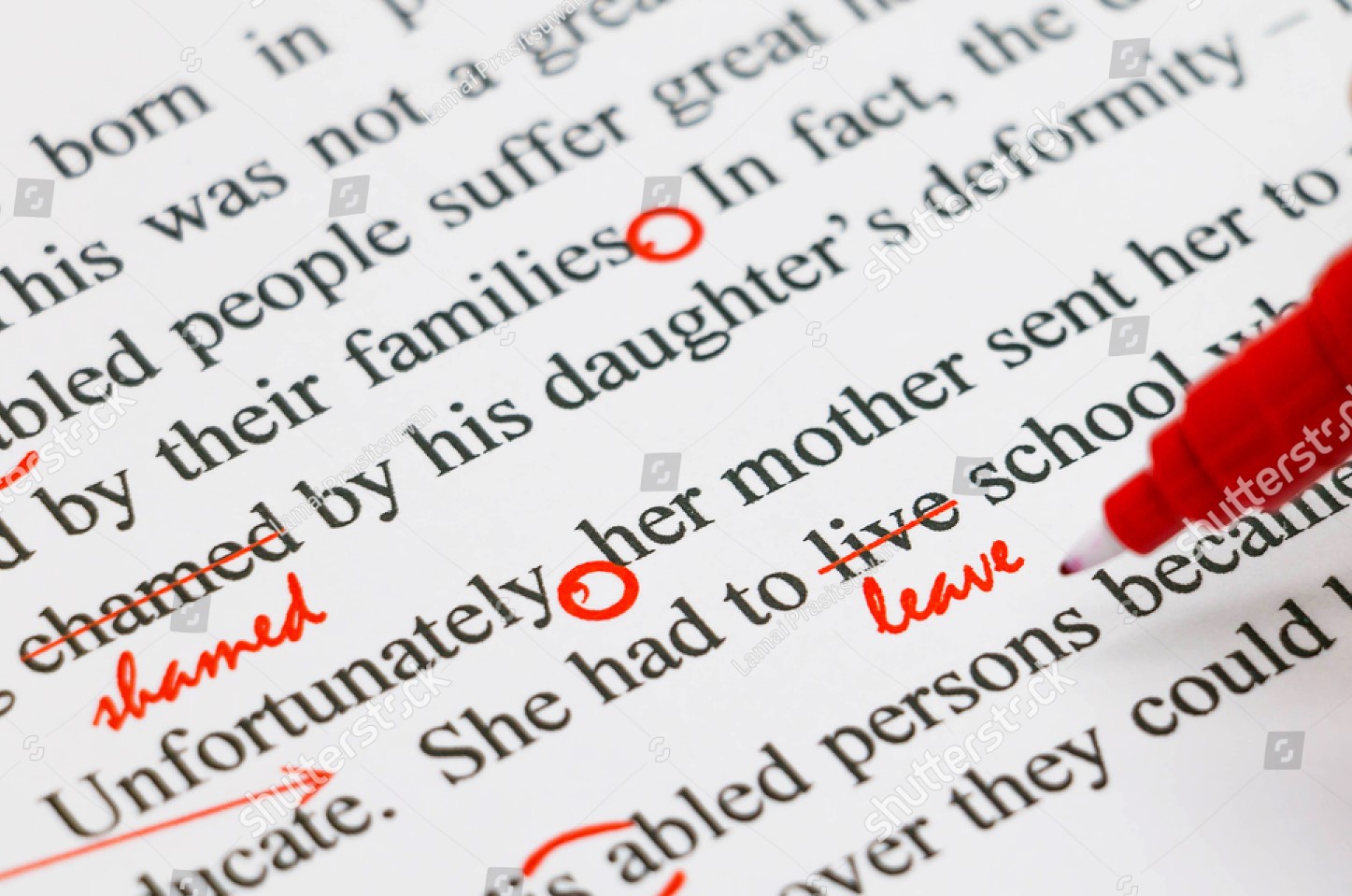

- Line Editing. And finally, the end is in sight, but there’s one all important picayune, yet critical, pass to be made. The line edit. The bane of some writers’ existence, a moment of ecstasy for others. No matter which camp you’re in, line editing is not optional. Every typo, punctuation error, grammatical faux pas, needs to be hunted down and remedied. Nothing hurts author credibility more than a sloppy manuscript, even one which is otherwise a page turner.

The methodology discussed is suggestive, not prescriptive. Over time, you will develop your own taxonomy and order for editing. Your efficiency will improve, but editing will always be a time consuming process. “Publication ready” is a vague term, and means different things to different authors, agents, and publishers. But, what is clear, is that there is one thing in your control as the one and only author—the quality of your submission. Getting a manuscript publication ready is a process, not a destination. Take the time to edit with focus. Do it in layers. Or ignore all of this, and do it all at once if you are the multitasker who can. But just do it. The end product will be more than worth the investment of your energies, and will enhance your word child’s chances of being seen outside the confines of your writing room.

*No matter how rough, bad, fit for the trash, this article assumes you have some words down on multiple pages, what some might call a “draft,” others… well. call it what you will, it’s where you must start your edit.

Hi Mandy,

You nailed it. I’ve attended so many conferences that I now have this sequence memorized.

Today, I’m P.O.’d because some Punctuation Gremlin has screwed with the punctuation rules, especially commas.I’m desperately seeking the new bible.

Heeeelp.

Elizabeth Kral

Hi Mandy,

You nailed it. I’ve attended so many conferences that I now have this sequence memorized.

Today, I’m P.O.’d because some Punctuation Gremlin has screwed with the punctuation rules, especially commas.I’m desperately seeking the new bible.

Heeeelp.

Thanks Elizabeth! Hope to see you this summer? Maybe we can discuss that punctuation gremlin then;-)

Mandy,

Onion analogy is perfect. Editing does sometimes bring me to tears as well.

Bobbi