I recently read with sadness that the school district my children attended was restricting certain titles from the library and removing them from the classroom shelves. Two of the books, The Diary of Anne Frank and To Kill a Mockingbird, were required reading when I was in school and even when my children were in school some twenty years ago.

I was appalled, heartbroken. For me, reading was often my life as I was growing up. It began with my parents. They were ranchers with only high school degrees, but they were both of Scottish heritage. For generations, their families had prided themselves on their literacy, education, and writing abilities. My parents easily fell into that family tradition. Both were voracious and indiscriminate readers; my mother was a fine writer and a dynamo editor. In our house, books crowded on shelves, and magazines and newspapers piled so high that we had to tiptoe to avoid triggering an avalanche. My father devoured westerns, especially Louis L’Amour books and the Independence series that encompassed all fifty states. My mother read Phyllis Whitney and Mary Rinehart Roberts, preferring mystery to romance. She stacked so many paperbacks by the bed that they served as her nightstand.

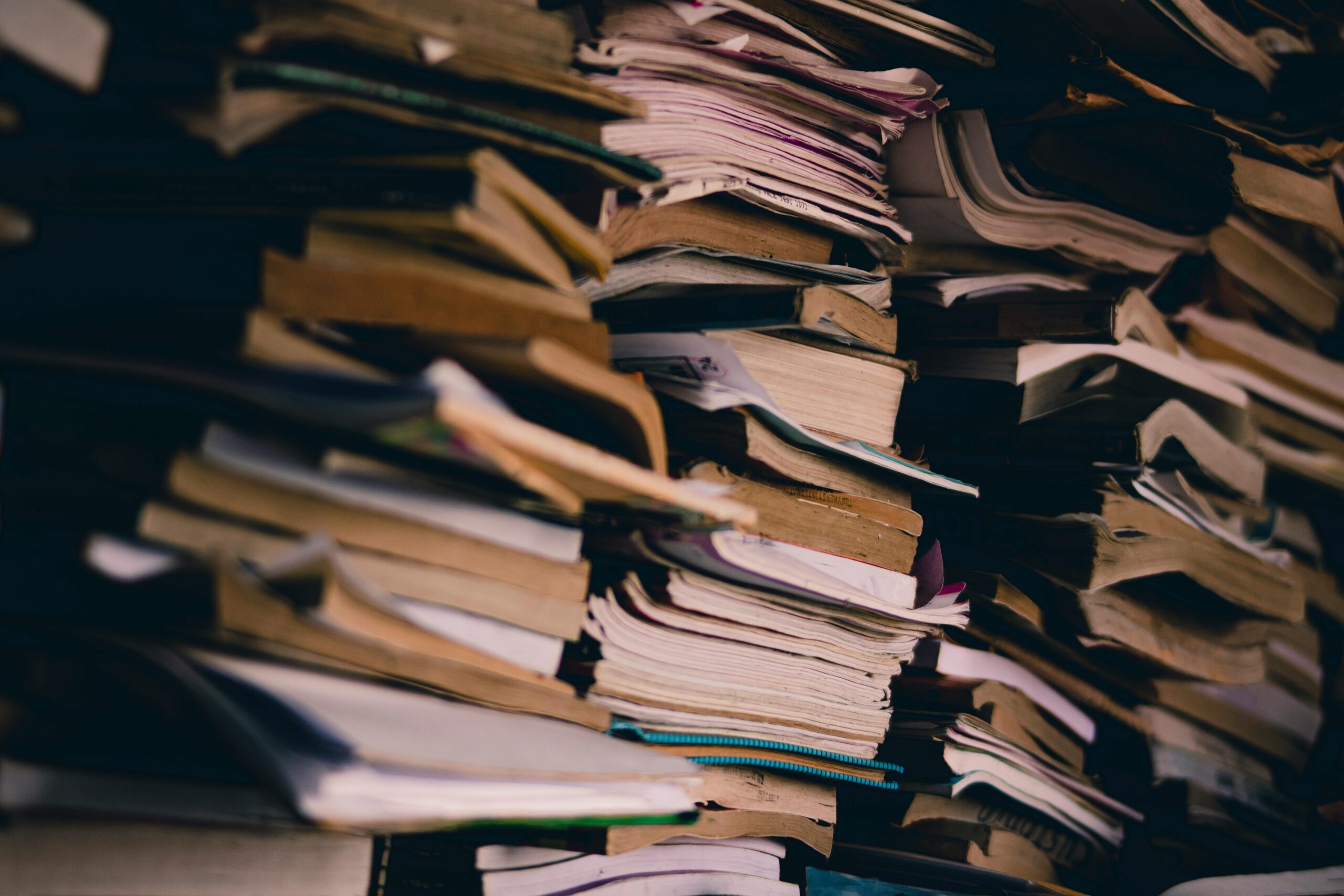

We kids had free rein to read whatever was available. And there was plenty. Our closest neighbor, who had grown up on a ranch a couple of miles away, was the superintendent of a mountain school district. Whenever books were discarded from the school library, he boxed them up and delivered them to us. Perhaps he thought that we couldn’t afford books on the limited funds we had, or perhaps we were just an easy solution to his problem. My mother cleared out an eight-foot-long jam cupboard for the books. She stacked them two deep on the shelves, and when those filled, she wedged more in the space between the top of the books and the shelf above. Our neighbor once brought five boxes to our house. Mom thanked him politely, but when he was gone, she took one look at the cupboard, with its doors that no longer closed, and just piled the boxes beside it.

Those books were a literary feast for my sisters, my brother, and me. There were picture books for kids, out-of-date textbooks and atlases, old encyclopedias, books on history, books on science, descriptions of plants and animals with gorgeous illustrations, novels, and books of poetry. One sister coveted the Five Little Pepper and Nancy Drew books, while I found a copy of Little Women. I asked my mother to read it to me at bedtime. For a couple of weeks, she complied, although for such a big book, it went pretty quickly (I suspect she skipped whole chapters and simply paraphrased the familiar story). Once, I tried to organize the mass of literature in the cupboard. I was quickly overwhelmed (or I started reading something and lost interest in the task at hand). Our private library never conformed to the Dewey Decimal—or any system, for that matter.

Our extensive choice of reading material at home prepared me well for Mrs. Brock’s seventh grade English class. I don’t know if it was her personality—she wasn’t a popular teacher—or if the textbook had been written by the hopeless and forlorn, but we read the most morbid stories that year: “The Most Dangerous Game,” “The Red Pony,” “The Scarlet Ibis,” “Flowers for Algernon,” and a play that we performed for our parents about extraterrestrials that invade a neighborhood. Fear and xenophobia escalate, until a homeowner finally shoots and kills an extraterrestrial. Bending over the body, he discovers that his foe is just like him. You nod, agreeing that the social message is valuable—except that it was somewhat lost as we seventh graders whooped and applauded when the executed extraterrestrial (a boy named Peter) squished a baggie of ketchup in his shirt pocket and then wiped his hand down his pants.

In high school, I did not belong in the “A” crowd (or “B” or “C,” for that matter). The school library became my refuge from the social mingling that took place in the hallways before classes began. While hiding there, I read Shakespeare and a lurid book on Lizzie Borden. I discovered Andrew Wyeth and the 1920s, an era that I love to research and write about as an adult. One summer, I read the classics before trying out for the College Bowl team (I didn’t make it, because the test also included—how dare they!—MATH). In college, I took a course from the Shakespeare Royal Theatre actor Tony Church, whose delivery was liberally peppered with the “f” word. I skipped lunch to listen to Dr. Gerald Chapman read the Iliad. When I was a junior, Iris Murdoch and John Bayley visited campus to give a seminar and speech. After graduating, I married and moved with my husband to Minneapolis. Before finding a job, I spent my days at the local community college, reading whatever classics I’d missed during my college years. I may have grown up, but I was never far from the little girl who used to ransack that jam cupboard.

I think now how much poorer my life would be if my early reading had been restricted by my parents, if we hadn’t been gifted that wealth of literature, if I hadn’t been able to openly peruse whatever I found in that overloaded jam cupboard. In the school district, parents must sign a permission slip before their children can use the school library. I suspect there are parents who won’t give permission, who will teach their children that books are something to be feared or avoided. I wish I could show those kids the jam cupboard, with its books crammed in every which way, falling on the floor, toppling down the nearby stairwell, covers and pages askew, and say, “Have at ‘em.”

Photo by Nothing Ahead on pexels.com.